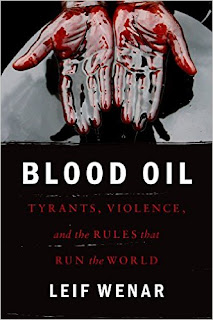

In last week's episode of EconTalk, Russ Robert's interviewed Leif Wenar on his new book, Blood Oil, about the impact of resource trade with tyrants and despots. Wenar argues that the current trade in natural resources, particularly oil, is not a true free-market economy because free markets depend on values such as private property. As Wenar points out, if I took over a corner gas station by force no one would suggest that I had the right to then sell the oil owned by that corner station because I don't actually own those resources. When we trade for natural resources with nations run by despots who separate their state's resources from their citizens--Saudi Arabia, Russia and Equatorial Guinea receive some analysis in the interview as different ways of doing the same thing--we are engaging in an unjust system which rewards pirates who steal resources from their rightful owners and corrupt the market.

In last week's episode of EconTalk, Russ Robert's interviewed Leif Wenar on his new book, Blood Oil, about the impact of resource trade with tyrants and despots. Wenar argues that the current trade in natural resources, particularly oil, is not a true free-market economy because free markets depend on values such as private property. As Wenar points out, if I took over a corner gas station by force no one would suggest that I had the right to then sell the oil owned by that corner station because I don't actually own those resources. When we trade for natural resources with nations run by despots who separate their state's resources from their citizens--Saudi Arabia, Russia and Equatorial Guinea receive some analysis in the interview as different ways of doing the same thing--we are engaging in an unjust system which rewards pirates who steal resources from their rightful owners and corrupt the market.Robert's is deeply impacted by Wenar's argument, but brings up concerns about both Wenar's somewhat interventionist-sounding plea that the government ban trade with such despots, pointing out that the criteria for a despot are somewhat subjective: why should we attack Equatorial Guinea's leader's savage exploitation of oil while ignoring China's more mild exploitation of labor? Wenar's main argument is that, while labor exploitation is bad, natural resources present something of a unique case. His arguments for this are good, but I would suggest a couple of critiques of both Wenar's solutions, and Robert's concerns:

First, I'd recommend that, rather than seeking to establish an objective criteria for how much despotism is too much despotism (at which point government sanctions need to take over), we would be wiser to mandate transparency: let the public know what they're buying (i.e. gas stations post what percentage of their oil is purchased from what market - Wenar intends to begin posting such data to his website in the near future).

Second, and this plays into the first answer: we need to acknowledge that there is a spectrum between despotism and ideal economic freedom: Robert's point about how to decide that Equatorial Guinea is too despotic but China is okay can be extrapolated to point out that the US isn't perfect in economic freedom, but it's a lot better than Equatorial Guinea. We need to avoid making the perfect the enemy of the good: by not regulating the outcome but requiring transparency from merchants the public can exercise subjective judgement about how much encroachment is too much, and the market can work against truly despotic situations like Saudi Arabia and Equatorial Guinea while exercising more caution in our treatment of China or the US.